In the 1920’s I had quickly built up a practice at the bar but, looking back, I took more risks than I realized. One risk I ran was to leave my legal practice and make the long trip to Europe. In those days the normal way of travelling to Europe was in the passenger lines a slow voyage which rising barristers did not dream of making for fear that their law practice would wither in their absence. After four years away at the war I had barely set my foot on the legal ladder when I decided to visit France again, and my friends were entitled to regard my trip in 1922 as the height of folly.

I had practically no money – just enough to make the trip with my wife. She was French and naturally was eager to visit her country again but one of my motives was trivial. I was irritated that, on leave in the south of France during the war, I had been denied admission to the Casino in Monte Carlo because I was in military uniform. As most gamblers know, uniformed men are not allowed into gaming rooms; it is said – I don’t know how truthfully – that this rule arose years ago when a high ranking soldier got into serious troubles at the tables. Now in peacetime the Casino was open to me, but my bank small, and my going away looked at askance by all interested in my future.

Between the two wars I made several trips to Europe, prompted more than once by a desire to improve the education of my son, Pierre, who had been born completely deaf. My wife was determined that he would have the best tuition in speech and lip reading, and thanks to her and a famous French teacher, Doctor Hoffer, he got it. Pierre went to Melbourne Grammar and then to Melbourne University where he gained two degrees.

Thence he went to Corpus Christi College Cambridge to obtain his doctorate. The rest of his life has been given to deaf education without regard to financial reward; and it is not too much to say that he has become a world figure in his field. His mother’s devotion had paid a handsome dividend.

My work at the bar, between the two world wars, was also broken by political campaigns, the first of which I entered almost frivolously and the second I entered as a crusader. The elections were about to be held for the Legislative Council, and the Hon Henry Isaac Cohen, K.C., who had been a Legislative Councilor since 1921 and had been several times a minister, was standing again. Shortly before the nominations closed I was waited upon by half a dozen individuals asking me if I would contest the election. Melbourne Province, of course, was a most conservative constituency. I thanked them with conventional phrases and said that I had no wish to sit in parliament.

An hour or two afterwards, walking through Selbourne Chambers, I met H. I. Cohen talking to three or four barristers. He interrupted his conversation to say to me, ‘I understand that this morning you were asked to contest the Council elections against me’. I agreed that that was so. ‘I hear you have declined’, he said, ‘I cannot tell you how wise you were. You would have had no chance against me’. I turned, went back to my chambers, telephoned one of the deputation and informed him I had changed my mind and would be a candidate.

The election was fiercely fought. My supporters worked like yeomen and at a late stage it became apparent that I had a reasonable chance of topping the poll. I received the usual awkward letters, including one from the Royal Orange Lodge asking what my religion was and what my views were on loyalty to King and Empire. I replied that I had been born a Catholic and had had no intention of changing my religion. Though not an ornament to the religion into which I was born, I said I would probably continue in it unless some good cause was shown to persuade me to act to the contrary. As for my loyalty to King and Empire I mentioned that I had been to the war and had been wounded two or three times, had been presented to His Majesty and decorated with the Military Cross. I trusted that they would find these answers satisfactory and so assure me of their support. The mistake I made was in giving my answer to them and not to the newspapers. As polling day drew near I became the subject of all sorts of canards – that I had been specially selected by the Catholic Church to win this prize Legislative Council seat; that Lyons was a Catholic and Prime Minister, that Hogan was a Catholic and Premier of Victoria, and that if this last citadel were captured the wicked old women of Rome would be triumphant. There were stories that I was a minion of John Wren, who was a power in the racing world, and there were other rumours which it is unnecessary now to repeat.

The campaign against me was virulent. Circulars were issued, and men were engaged to go into every corner of the electorate to warn the electors against the perils which threatened them. I had, on nominating, informed the world that I did not propose to solicit support from any organisation. I was approached by the movie picture industry and others and asked whether I would accept assistance, but I knew that beneath the request would be some future demand. I maintained my complete independence.

Election day was cold and damp, and I saw my opponent’s cars from early morning dragging to the election booths old people who had not left their home for years. I realised that I need not await the counting of votes to know the result. Strange to say I obtained a total of votes which exceeded that of any previous winning candidate. But I was still defeated. I felt that I partially squared the ledger when the day came to return thanks to the electoral officer. After my opponent had spoken I grabbed him warmly by the hand and addressing the assemblage I said that there never had been an election more fairly contested, that throughout the whole of the campaign I had not found one single episode of which I could complain, and that not one streak of unfairness had embittered the contest. I congratulated him on fighting so clean a fight. My discomforted opponent sought to disengage his hand but I held it firmly until he commenced to blush from his nose to the back of his neck. Meanwhile I poured encomiums on him and all who supported him and expressed the hope that every election conducted in Australia might be conducted in such a fair spirit, without any of those taints which sometimes disfigure an election contest.

That was the beginning and end of my electoral experiences. Had I been elected I feel sure it would have had an adverse effect on my life. It certainly affected the legal career of the successful candidate. Cohen was a completely competent barrister but rather inclined to labour six bad points than to concentrate on one good point. After this election his practice deteriorated in a surprising fashion. He and I became firm friends as the years went by, and I was sorry to see his Bar practice dwindle.

Many times since that election I have been requested to join various worthy bodies fighting for some cause or against some evil. I have never doubted the genuineness of those submitting the request to me but I have nearly always asserted my independence, feeling it was unwise, by either personal or pecuniary support, to associate myself with objects or causes over which I had no control.

Primary Producers Restoration League – 1932

I was caught up in one other political campaign, and this campaign, I like to think, helped people who were in difficulties. The world depression was raging. In Australian cities more than one quarter of the breadwinners had no work, and on the farms the people had plenty of work but for many their income was too small to meet even their meagre needs. Prices of wheat and wool and all crops were low. Payments of taxation to the government and interest to banks pressed heavily on most primary producers. The security of farmers was threatened by mortgages, and many families were forced to quit farms into which they had put such hope and hard work.

Late in January 1932, while travelling on the Bendigo Express, I chanced to meet Hector McKenzie. He was a magnificent man, a first class auctioneer, a member of a stock-and-station firm in Echuca, and a staunch friend to all in difficulties, even to the extent of seriously endangering his own financial position, His integrity was universally accepted and he enjoyed the trust of all who knew him. During the journey from Melbourne to Bendigo we discussed the plight of people on the land and decided that I would convene a ‘monster’ meeting of delegates from all primary producers’ organisations. Arthur Rodger, an experienced politician, was told of our plans and decided to join us. Rodgers had once been, like McKenzie, a stock-and-station agent and was now a farmer and grazier, so he understood in stark detail the rural crisis. Though he no longer sat in the federal parliament he had long represented the western district seat of Wannon and had been minister for trade and customs in Billy Hughes’ final ministry. I had taken Silk in 1929 and had a busy practice but decided to campaign vigorously for the primary producers. As a result WB set up an organisation called the Primary Producers’ Restoration League. I was its president, Hector McKenzie the vice-president, Arthur Rodgers the manager, and a well known Melbourne solicitor, Arthur Phillips, agreed to become treasurer.

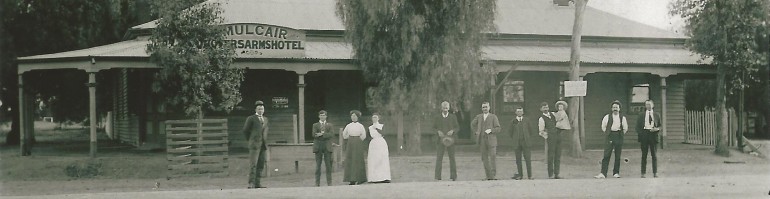

The inaugural meeting of the crusade was fixed for Friday 10 June 1932 at Goornong. My old town had its greatest day. Once possessing three hotels, it now barely supported one hotel in addition to the blacksmith’s shop and general store.

The town’s existence was so little known that The Herald had to draw a large arrow on a map of northern Victoria. After this lapse of time it is difficult to describe the fanatical support

we received from landowners. Even the police had to be called in to direct traffic, and the local hall was quite inadequate to accommodate the crowd. Arrangements were made to broadcast those without seats and thus the Primary Producers League was inaugurated.

Our declared objectives were to maintain primary production by –

(a) reduction of interest to primary producers;

(b) creation of tribunals to deal with relationships between primary producers and mortgagees and unpaid vendors;

(c) to ensure security of tenure for mortgagor primary producers;

(d) to procure relief under financial emergency Acts.

“The great need today”, I told the gathering, “is to raise in Victoria a sense of national danger. Every man and woman must be prepared to assist our primary producers for, great as our other national and individual problems are, the greatest are those which today assail and burden the body responsible for national security and solvency – the primary producers”. At this meeting I emphasised that farmers did not desire to smash financial interests but to save them. They desired to cut off a toe to save the leg. During the great Land Boom crash of the early 90’s a majority of the Banks had reconstructed but farmers – who were seeking and to do no less – were being denounced as repudiationists. At one stage the relationship between the Movement and the Country Party was considerably less than friendly. It was not helped by my unwise denunciation of the Party as a collection of venerable and decrepit old gentlemen.

The farmers who came in droves carried the following resolution:

“To Prime Minister, Mr Lyons: Yesterday enthusiastic meeting at Goornong of 1,000 primary producers and land holders founded Primary Producers Restoration League and requested you to broadcast a Continent wide appeal to mortgagees and financial interests to refrain from any action forcing producers off the land. Kindly convey this message to the Premiers’ Conference. Eugene Gorman, President”.

Here is the Bendigo Advertiser’s report: ‘Goornong had its most memorable public meeting today when the Primary Producers Restoration League was formed at a gathering which overflowed from the hall into the street. A special train brought delegates from Echuca but many more farmers came in motor cars from Shepparton and Kilmore and business men attended from Melbourne, Ballarat and other country towns (30th June meeting.) The meeting provoked leading articles in the prominent papers. The Agricultural Society joined in our support.

Arthur Rodgers had a flair for publicity and issued daily bulletins which were printed as though they came from Army Headquarters. The Melbourne Sun applauded us. The Age newspaper was generous with its space. It was soon obvious that primary producers were inflamed to a point which would considerably embarrass their official parliamentary representatives the Country Party. John Allan was its leader but no one was quicker to realise our threat to the Country Party than Albert Dunstan, its deputy leader and later the Premier of Victoria. Our intelligence service reported that he had urged the Bendigo newspaper not to give too much publicity to the Goornong meeting. His effort failed and we received full-page reportage. John Lienhop, later Sir John, the Victorian Agent General in London, was present and became a great supporter. The movement attracted interest not only throughout Victoria but also in the Riverina.

Every district responded to our agitation, and reports flowed into the Melbourne press from every country town. I addressed gatherings almost daily, remaining in Court until about 3.30 p.m. and then motoring into the country. I urged the farmers we met: ‘Do not leave your land, stick to it, stick to it. Otherwise you and your sons are likely to become wharf labourers’. Banks, trustee companies and insurance companies, who did not favour a reduction of interest rates, were gravely concerned. We three leaders were looked upon with almost as much suspicion as a subsequent generation felt towards extreme Left Wingers. There were exceptions. Alfred Davidson, who was general manager of the Bank of New South Wales and an individual whose views – for a banker – were radical, waited on me to admit the validity of our objectives but with a plea not to go too far. The A.M.P. Society gave a sympathetic hearing to our argument urging the reduction of interest, but the National Mutual Life Association had been shocked by our audacity and gave us a categorical refusal. I decided to publicise their attitude. I addressed a meeting at Echuca on the usual lines and having emphasised that no landowner could possibly make a profit under existing conditions, exhorted my hearers to breed a few sheep dogs, preferably with a slightly savage strain. I asked that these dogs be kept until prosperity revived and the agents of the National Mutual arrived at the farm to solicit business. On that day, I suggested, the dogs might be let loose.

My suggestion was received most unkindly by the institution in question and I returned to Melbourne to find much discussion as to whether proceeding should be launched against me for defamation. Wiser counsels prevailed, and no action was brought. The stock-and-station agents, butchers, grocers, and exporters met at Newmarket. The three of us addressed the meeting and old Mr McNamara, the doyen of stock agents and a member of the firm of John McNamara & Co., personally guaranteed the subscriptions of all Newmarket stock agents. ‘We have quite enough Parliamentary representatives already’, said McNamara firmly. ‘This is not a new political party. What we want to

do is to make those already in Parliament work’.

The Country Party proclaimed that our League was unnecessary and that it was the only guardian of country interests. Soon, however, it became clear that nothing could stop our progress. Albert Dunstan, who was one of the most astute politicians Victoria has known, decided to join what he could not beat. He caused an invitation to be sent to us to meet the Country Party in its room in Parliament House to receive thanks for what we had initiated. Underground sources informed us that the proposal was for the parliamentarians to laud our efforts for a few minutes and then resume the business of the day.

I and my two colleagues were warmly welcomed by Mr John Allan, a former Premier of Victoria and a northern farmer. He explained that we had been called so that his party could tell us just how much our organisation was appreciated. He then invited me to speak. I asked whether I was at liberty to speak with frankness or whether I had to behave myself as though I were in the drawing room of a casual acquaintance. He· assured me that he wished me to speak freely. I said that the invitation to attend was appreciated but would have been much more so had we not known that his deputy, Albert Dunstan, had used every opportunity to thwart our League and that he was constantly detracting from our efforts. At once Dunstan leaped to his feet and, in his shrill voice, protested bitterly. I picked up my hat and, addressing Mr Allan, said that.my opening words were a response to his statement that I was at liberty to speak freely. Clearly, I said, this was not the view of all his colleagues. I thanked him for having received us, and left the room. As a result their meeting lasted until after midnight.

News that something extraordinary had happened reached the reporters. I said nothing, and my colleagues said nothing. About midnight a peace treaty was about to be offered to us by the Country Party. I was taken in and some form of armistice was signed. From that day onwards Albert Dunstan and myself developed a rather satisfactory friendship. It is only right to say that had Rodgers, McKenzie or myself wished to stand for a Country Party seat there would have been little doubt of our election but in order to allay the fears of the Country Party the three of us went on the platform and announced that none of us was a candidate for Parliament nor under any circumstances could we be induced to become candidates.

The government passed legislation on the lines we had advocated. A moratorium was declared under which debtors could submit their cases to a tribunal. It is not too much to claim that some thousands of men were enabled to remain on their land through our League; and I am sometimes very pleased, at a gathering, to meet a farmer who is kind enough to admit the debt that he owed to our efforts.

My place, in the eyes of vested interests, was fixed for at least the next twenty years. I was regarded as unorthodox and unsafe and any suggestion to appoint me to a directorate was frowned upon. It was not until much later that I became chairman of the Australian Board of the London Assurance and chairman of the Australian Board of Unity Life.

For men on the land and for those who supported them, the pressures during the depression were harrowing. My fellow campaigner, Hector McKenzie, did not escape them. Hector and his brother Hugh had enjoyed a high reputation. Businessmen in Echuca, they were unable to resist the borrowing claims of men

of whose personal merit they had knowledge. Like the country store-keeper of the day they carried an unfair burden, the bulk of which they should have unloaded onto a larger institution. Instead they had their own substantial overdraft with the ESA Bank, and in turn they lent those funds to men on the land. During the depression, they were called in by the bank and notified that the large overdraft could not continue. They assured the general manager of the bank that they would cut the overdraft, only to be met by the sardonic comment, ‘How can you possibly reduce this figure?’ They set to work and accomplished the impossible.

Unfortunately the McKenzies failed to learn fully from this experience. Once again, when money became short, their clients came to them for finance. Again the overdraft grew and this time the blow fell. One morning they received a curt intimation from the bank that none of their cheques – and they had many in circulation – would be paid after 3 o’clock that day. It is difficult to believe that this was not their fault but in fact it was not. They called on me in great perturbation. I had a retainer from the ES & A Bank, and I immediately returned it and indicated that I proposed to act for the McKenzies. An appointment was arranged immediately with Clive McPherson, of Younghusbands, who rose to the emergency. He notified the McKenzies that all their sales were to proceed and that arrangements would be made to meet their cheques. This was done; their reputation was preserved; and they retained the affection of thousands of people until they died.

To the credit of Albert Dunstan this story must be told. By chance a vacancy occurred at this time among the Commissioners of the State Savings Bank. I went to Dunstan and pointed out that Hector McKenzie and his family had for years helped Victoria, and that nothing would do more to restore his prestige amongst the men on the land than for him to be appointed a Commissioner of the Savings Bank. Dunstan promptly appointed him. A reasonable yearly fee went with the post, but that was a minor advantage beside the expression of public confidence implicit in his appointment.

I was a primary producer of sorts in the depression. My father had the countryman’s longing to a few acres, and he induced me to provide money to buy a few Sheep for the small property of one of the family. This venture was far from successful, but having bought the sheep I was later persuaded to acquire a small lucerne farm saddled with first and second mortgages. It so happened that the moratorium which the Restoration League had placed on the Statute Book provided for the postponement of mortgage payments which otherwise would be immediately due. Although I strongly supported the moratorium I had too much vanity to resort to it personally. A Rochester solicitor – possessing great integrity but less humour – was obviously worried about my connection with the Primary Producers Movement, and he wrote me what I thought was a rather injudicious letter, primly pointing out that my second mortgage would be due in the course of a few weeks and expressing the hope that I would not resort to the moratorium. I was irritated, and in reply said that I had not yet even considered applying for a moratorium but that I was the owner of a fast mare, Bon Cretian, which would race during the next week or two. I told him that I had confidence in the animal’s ability and honesty and proposed to back her for sufficient money to pay off the second mortgage and that I hoped both of us would benefit from

the race. I was later very friendly with this solicitor but my letter provoked him to bursting point. He promptly replied, expressing himself with considerable freedom.

Bon Cretian was to run at Moonee Valley. On the day of the race I was engaged in cases at Ballarat and the possibility of reaching the racecourse in time seemed remote. I gave instructions that if anything happened to me through excessive speed in the car, the horse was still to run and the money was to be placed on her. I then engaged an extremely fast motor driver – fast for that era – to take me to Ballarat. I remember achieving fairly satisfactory results from the cases in the Ballarat Police Court, but when I left the court the time remaining for the journey of 70 miles to Moonee Valley seemed too short to enable me to see the race. We travelled at a terrific pace and, miraculously, arrived at the course just as the horses were going to the start. I remember Jardine the cricketer was there, and as I went to the grandstand I was introduced to him and advised him to cover some of his Australian expenses by supporting my horse.

It was a memorable day. I had £500 on the horse and that represented, to me, a considerable sum. But my mare did her duty, and I won something over £2,000. The mortgage money

was duly paid; and as a final gesture I instructed my solicitor to pay in bank notes and not by cheque.

Bon Cretian was my first racehorse. She was by Hurry On out of an English mare, and I leased her from Sol Green. She was trained by Dave Price who was a competent trainer, a real adviser to me, and a man of whom I retain affectionate memories.

One day Price informed me that my horse was entered for a maiden at Cranbourne and could not possibly lose unless a dog ran across the course. As Dave was a conservative man, and language of this exuberance was unusual, I invested – I forget exactly how much – a couple of hundred pounds on her. She won by the length of the straight. Encouraged by her success I from time to time bought other horses, and although I doubt whether my turf adventures finally returned a profit I did have a great deal of success.

Bon Cretian had terrific speed but an apple knee which made her run wide at the turns. In one race, ridden by Pat Tehan, she started from an outside marble, ran to the outside fence in the straight, was pulled up by her rider who set her going again, and she finally won by a length and a half. Her last appearance was a tragedy. At Warwick Farm, ridden by Maurice McCarten, she had won brilliantly, and I then kept her without racing for a long time while I waited for a six-furlong race up the Flemington straight. I remember my wager at Flemington; I had £3,600 to £400. I could dispense with the £3,600 – it was the £400 that mattered. The stable started two animals, the other being Vautry at 25/1, to which we gave no chance. I didn’t even bother to have a saver on it. You can guess the result. The outsider Vautry beat Bon Cretian by half a neck and I lost £400 instead of collecting £4,000. For a moment I was somewhat less than gay, but then I thought, ‘My boy, you once made a resolution; you got out of the war without any disabilities’. So I walked down to speak to Dave Price, my trainer. “Well, Dave”, I said, “you really brought off something – first and second at Flemington”. The poor old man looked at me as though I had taken leave of my senses the defeat of Bon Cretian was a blow to him. At any rate, I felt that I had kept a resolution taken under more precarious conditions.

Charles Fox was just up to weight-for-age class and performed brilliantly; Jack Hill had bought him for me in Sydney for a few hundred guineas. I also owned John Wilkes, winner of the Melbourne Stakes, winner of the Williamstown Cup, winner of

a weight-for-age race in Sydney, a 2/1 on favourite for the A.J.C. St Leger. Though I needed money I had refused offers for

£3,000 and £4,000 for the horse. As the horses were going out to race in the St Leger, a well-known trainer said, “I understand you want £5,000”. I said, “Yes, that’s the price”. He said, “I’m buying him for Mr White of Queensland”, but he added “you want him to run for you in this race”. “Oh, yes”, I said, “he must run for me in the Leger”. “Well”, he said, “he must pull up sound”. “Certainly” said I, “that is most reasonable”. Breasley, my regular jockey, was unable to take the mount and Maurice McCarten rode him. Things did not go well during the race and within five yards of the winning post he faltered and staggered to a dead heat. The horse now had a serious ligament affliction, and the sale was impossible. Instead of collecting my £5,000 I received only half the prize-money and a disabled horse.

Once again I fortified myself with that resolution made in the trenches and was able to crack jokes. I hope that the nonchalance I displayed was sufficient to hide from the public the gravity with which I viewed this unfortunate happening. I have tried from this and other experiences to persuade :friends and acquaintances of the futility of worry; I regard worry as an acid, devastating in its consequences.

My favourite horse was the country champion Prince de Conde with whom I won races everywhere in Victoria. He won, I think, nineteen out of his first twenty-two races and I had tremendous enjoyment from him. Des Judd trained him and Les Whittle always rode him. Over his stall at Judd’s stables at Kambrook Road, we used to put a number for each win and the stall also carried his name, Prince de Conde of Kambrook. I did not win a lot of money – I was merely trying to win races – but his name is still frequently referred to by the older members of the racing fraternity. With partners I was associated with Circuit Fee which won four races as a two year old but who trained off and never repeated her good form as a three year old. Later I acquired a Court Sentence filly from Hilton Nicholas which I named Pour La Vie and up to date she has won three races in succession. There were a number of other animals – I have photos of many of the wins – but their performances were no more distinguished than those of scores of other winning horses.

Streperus was a brilliant horse whose merit is not reflected in his turf record, although I won a few races with him. He appeared a winner on many occasions, only to pull up before the post was reached. The stewards became concerned at his erratic form until one day they saw him led into the dismounting yard with blood pouring from his nose. Eventually he died in a race and it transpired that he was an internal bleeder. With Strepherus I had the unique distinction of winning the only weight-for-age race run at the old Ascot racecourse. He had let us down badly a few days before at Geelong in a minor race, and I didn’t even go to Ascot to see him run. He galloped like a champion and won convincingly. Needless to say I hadn’t invested a penny on him.

One horse I raced was named Royal Armour. He was not a champion but won quite a few races, including the King’s Jubilee Cup. On Saturday l June 1935 he was to run at Flemington in the Sandringham Handicap, and Scobie Breasley was to ride him. Old Dave Price who trained him was confident he would put up a decent performance, Recently a blacksmith had accidentally driven a nail into his hoof, which had caused him to lose a few days training, but we thought this injury had been overcome. I had £195 on him, a very large bet for me at that time, but the horse ran poorly and finished near the end of the field. He was also entered for a race on the Monday- the King’s birthday holiday – and when I instructed Dave Price to go ahead and race him, Price was startled. “But Mr Gorman”, he said, “If this horse should happen to win they will pull the grandstand down”. My obvious reply was that I didn’t own the grandstand and that, having backed my horse on the Saturday, I claimed the privilege of racing him when I thought fit. I had nothing to be ashamed of.

The horse took his place in the field for the Birthday Handicap on Monday, and the contestants proved even weaker than was originally expected. On this occasion Breasley could not ride the weight and Stan Tomison took his place. I had £30 or £40 on him in case he might come home. He not only won but had the field at his mercy three furlongs from home. It was one of the rare occasions when hooting began, not as the horses weighed in, but when the winner was still a furlong from the post. The punters howled for blood. Poor Dave Price, who was not a young man, was greatly perturbed until I instructed him to retire to the weighing room while I accepted the jeers.

I can truthfully claim and without affectation that it was one of the most exhilarating moments of my life: not that I would seek a repetition. I knew that I had backed the horse solidly on the Saturday, and I knew that neither Price nor Breasley had been a party to any wrong-doing, and so my reaction to the uproar was completely cold. In addition I was solaced by the fairly substantial stake which the horse had won.

That night The Herald called for ‘Open Enquiries’ and commented caustically on the reversal. As usual I was invited to give an explanation which might pour fuel on a controversy which was well suited to the needs of journalism. I refused to say anything until the following Saturday when a paper known as ‘The Circle’, owned by that charming sportsman Herb Rothwell, made its appearance. Herb, of course, was delighted when I volunteered to write the story for his little paper. I told how much I had placed on the horse in each race, naming the amounts and the bookmakers and odds. I told how on the Saturday ‘every uncle, cousin and family connection from Bendigo to Echuca staked his or her maximum’ on Royal Armour and accordingly had lost. And then I concluded with these thoughts:

“That the reversal of form was marked I cannot deny. That the public were justified in expressing their amazement I will not argue against. That an enquiry was called for is undeniable – and I called for it. Whether evidence given at stewards’ inquiries should be made public is fairly a matter for diverse opinions, and I take no objection to the case for publicity being argued by any racing writer.

My sole complaint goes much further. I have for long deplored the tone of a great deal of so-called sporting journalism. Under the pretext of ‘protecting the public’ there was for some time past been a veritable orgy of ‘sensational’ slush published, such as any hack could turn out by the column.

I know at least six men well able financially to race a horse and inclined to do so. They will not, because, rightly or wrongly, they are afraid of the risks of ownership. The current view of racing has

also become distorted – and I fear from the same source. Every favourite that fails is ‘dead’, or, if he wins, it is ’because there was no opposition’. The whole atmosphere of racing is becoming nauseous. Certain well known owners continue to race solely because they have studs or racing interests which necessitate their doing so. The advent of a new owner is an event.

There are many owners and would-be owners without my experience or particular brand of philosophy. Their only solution for unmerited criticism is either to get out or stay out.

To conclude, racing journalism is not without its own debt to the sport which maintains it, and the public should be educated ‘up’ and not merely written for under harsh necessity of satisfying the circulation manager.

To revert to Royal Armour and his tribulations. I have not a scintilla of regret for having started the horse on Monday, save only that which arises from any undeserved reflections on Breasley or Price. Hoots have one advantage over cheers. One sometimes suspects the bona fides of the latter. He is always sure of the sincerity of the farmer.

My opinion of Breasley I will indicate on the first occasion I have a chance of putting him up on one of my horses. Price, I have already said, is my friend as well as my trainer.

Royal Armour’s feet are at the moment a source of trouble. The first day he can race he will take his place in a field, as my lease expires in December, and never will I allow his position at the end of a race to influence his acceptance of his next engagement – I am, yours sincerely,

‘G. ORNONG.’

The moral is simple. Until horses learn to talk we shall never know with certainty why they perform erratically. But when horses do learn to talk, all betting on racecourses will become pointless.

‘Mousey’ was one of my colorful clients and his father was responsible for one of my minor turf triumphs. His surname does not matter; his nephews are professional men in other States and they may not cherish the memory of their late uncle as others do. The time factor is all-important in family traditions. Even devoted sons are not amused by stories of a father who achieved notoriety as a confidence man, whereas great grandchildren are more tolerant. ‘Mousey’, as a young man, operated as an S.P. bookmaker in the north west of Victoria, but the public service he provided on hotel premises was one day interrupted by gaming police. I, as a very junior barrister, was offered a brief to defend him at a substantial fee. It was so large that my inability to accept it caused me much regret.

The law, as it then stood, necessitated proof that the S.P. bookmaker was pursuing his calling with the knowledge of the hotel licensee. This loophole is alas no longer open. I advised as to the legal position and Mousey’s defence was entrusted to another barrister. Justice was done and the case was dismissed. Six months later I received a letter from Mousey’s father telling me he had a horse running in the last race at Caulfield. He suggested I should wager on it.

My means were slender, but my credit was high. Since I started wagering ‘on the nod’ at about the age of 16, I had been a punctilious settler; I learned this lesson early. With mingled hope and fear I paid my entrance money at the racecourse and engaged in the weekly battle. Every experienced race-goer knows only too well the problem of trying to acquire a ‘bank’ to put on the good thing, and on this day I wagered carefully and fearfully, and when the last race came on I had accumulated the large sum of £37. I still remember my mental processes. Would I keep the £37 or would I joust with destiny? Finally I jousted. My first wager was £500 to £25. “Why I decided to go even further I do not know, but my £37 profit was converted into a potential loss of £13 when I took a second wager at £500 to £25. A third wager lacked any · shadow of justification, but as the horses went out I booked a further £500 to £25. In the straight the race developed into a neck and neck struggle between my horse and one trained by Jim Scobie. All this happened long before photofinishes were thought of; and few spectators knew what had won; but up went the number of my horse. I left the course with £1,537.

On the Monday settling I called in at Drummonds, the jewellers, bought the finest set of decanters they had on display, and presented them with a suitable inscription to my benefactor.

How Mousey fared on the race I do not know, but after a brief but spectacular career as a bookmaker in Australia he went to England where his fortunes fluctuated. Many years later he visited Australia, having first informed a well known Sydney businessman that his sole object was to bring off a coup on a horse running at the Melbourne Cup meeting. The two came over for the race.

The horse selected was owned by Eric Connolly. Mousey requested his acquaintance to do the commission for both, and specified £2,000 for his own wager. Much to Connolly’s chagrin, the price shortened considerably without any stable support. The horse duly won. Mousey left for England within a week, his friend providing a couple of cases of champagne to assuage the tedium

of the sea journey. Of course, if the horse had not won, Mousey might well have vanished rather than come up with his share of the losses.

In the following year a horse of Connolly’s was again the medium of the plunge and again the ‘market’ was taken. I forget the exact sum invested on Mousey’s behalf by his commissioner friend, but from memory it was £3,000. Unfortunately the horse lost, and shortly after the race Mousey had to advise his friend that an expected remittance from England had failed to arrive. The victim reacted badly and caused Mousey to be arrested and to be charged with obtaining money by false pretences. I was retained to defend, and Mousey was committed for trial. As he and his solicitor left the Police Court with me I suggested that he must be feeling a little despondent. ‘Not at all, Sir, not at all’, was the reply, ‘A cold shower this morning, a clean suit of clothes and the world is before me’.

There was no substance in the charge as laid. Legislation making racing bets recoverable at law had not yet been passed, a state of affairs which the Crown soon acknowledged, and a nolle prosequi was entered. Mousey returned to England, but this time without the champagne. Some years later Mousey paid another visit to Australia, and another legal arrow was fired at him by his former colleague. Again we had little difficulty in rescuing him.

The years flew by. I was often in England, and my last meeting with my client was an accidental one in the Strand. He was in poor health and was no longer the dapper, insouciant man I had known. He asked for a ‘pony’, in other words he wanted £25. I was contributing handsomely at this time to the credit entries of my fellow members of the Portland Club and would have myself appreciated a few ‘ponies’ but I could not decently forget the day at Caulfield which I owed to his father. Mousey received his ‘pony’. He died soon afterwards.

I have seen many of my friends, acquaintances and clients hit the high spots, but few keep their place when time and illness dulls their intellect and when they feel the strain resulting from their long extravagances.